Edson Athaíde, Advertising Executive

The title of this article stems directly from two supposedly antagonistic universes: reality and fantasy or, should we so prefer, the rationale of the abstract.

The bean is a foodstuff, which is planted, comes from the earth, that we eat, which has a price, weight and physical existence.

The dream is, well, a dream is just that: the oneiric, that which has neither head nor feet, no end and no start, as the dictionary states: utopia, reverie without justification, a chimera of brief duration.

“Reason and heart”, as my uncle Olavo would say to recall how the complementariness of opposites tend to be mutually seductive.

Whoever speaks of beans might also say potatoes, cars, computers, clothes, airplanes. The economy is beans, the market is beans, the state is beans, marketing is beans.

Whoever speaks of dreams may be also be talking of cinema, theatre, literature. Fashion is dreams, music is dreams, art is dreams, culture is dreams, creativity is dreams.

“The Bean and the Dream” is the title of a novel published in 1938 by Orígenes Lessa, a great Brazilian author who was also in advertising.

The book tells of the hardships of a writer who dreamed a lot but earned little, neglecting the needs of his family and leaving his wife to play the role of the bean, struggling to ensure there was food on the table.

I always recall this book and Lessa whenever I get asked to write about what there is of art in advertising.

There is a lot. There always was and there always will be.

What turns advertising into an art ‘per se’? It is not and never shall be.

“Advertising is sales talk set down in writing”, summarised one of the founders of modern advertising. However, for this sales talk to be persuasive, it needs to be very well written.

And that’s where the art comes in. And up step individuals such as Orígenes Lessa, Fernando Pessoa, Ary dos Santos, Luís Fernando Veríssimo and so many other writers who spent time in advertising.

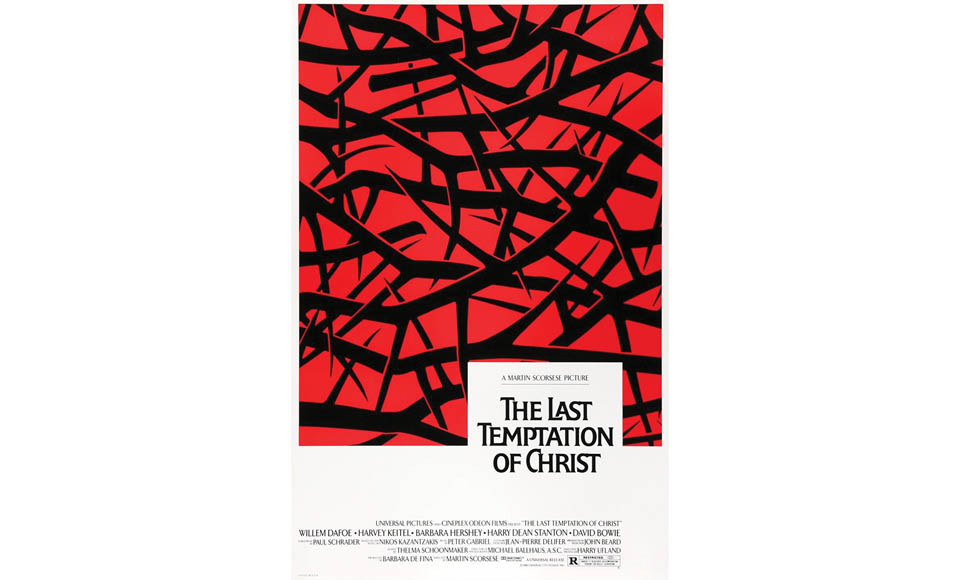

However, we also cannot overlook all the painters, sculptors, filmmakers who were or are working in advertising. Just in case you didn’t know, Spike Lee owns an advertising agency as does the actor Ryan Reynolds. Scorsese has made various adverts. David Fincher still does.

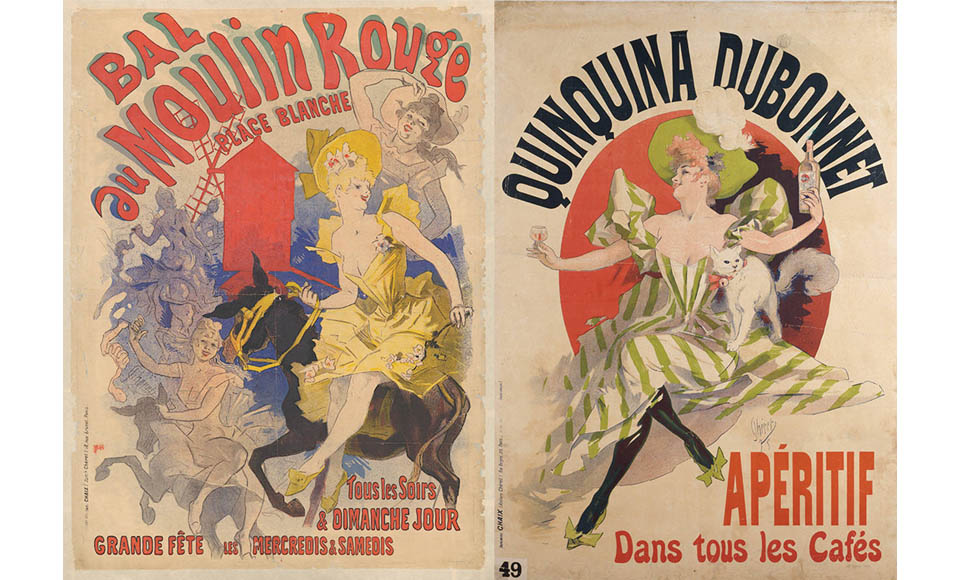

At the end of the 19th century, the owners of Parisian cabarets asked artists to come up with posters extolling the virtues and excesses of the shows they were staging. Toulouse-Lautrec paid many of his wine and absinth bills by producing posters.

The tomato soup cans by Andy Warhol clearly portray the almost incestuous relationship between the Fine Arts and advertising culture. The Campbell Soup Company could not have dreamed up a marketing strategy better than that created by Warhol to render such a banal product into the minds of American society for all of eternity.

Among the many definitive phrases uttered by Andy Warhol is that stating: “When you think about this, department stores are like museums”. ‘Touché’.

Keith Haring loaned his talents to posters for Absolut vodka and for Lucky Strike cigarettes; hence, acting in the trail of the painters Edward Hooper and René Magritte. The genial illustrator Norman Rockwell went further: he lived basically off selling his designs to commercial brands (and thus helped shape Father Christmas in a classic advert for Coca-Cola).

Nevertheless, being a genial artist is no guarantee of success in the advertising world. Salman Rushdie, for example, tried to become a copywriter but failed the test. Scott Fitzgerald was a merely average copywriter. The great Brazilian poet Paulo Leminsky created mediocre adverts. The Portuguese Alexandre O’Neil may have come up with some memorable slogans (“There’s seas and seas, there’s the going and returning”), but nothing in comparison with his literary works.

Artists and advertisers may even sit down at the same table but they are not necessarily the same persons.

Which brings to mind a legend (perhaps true) of an event that gets attributed to our Orígenes Lessa from the beginning of this essay.

Impressed by the success of a campaign for the Fechadura Brasil lock company, the marketing manager for Gessy soap sought out the agency where Lessa worked and made a request:

– You know the slogan that goes “Fechadura Brasil. Fecha e Dura (Closes and Lasts)”? I want something that sounds as good for Gessy.

Orígenes thought he had understood the task and he set about his work. The following week, he put forward some options that were rejected on the spot. He humbly continued working on alternatives throughout months, without ever coming up with anything that fully satisfied the client. Then, one day, at a meeting, he suddenly exclaimed:

– I now know what can be our “Fechadura Brasil. Fecha e dura”!

They all looked at each other and awaited silently for this moment of pure art and genius that was about to happen.

– “Sabonete Gessy. Sabo e nete! (meaningless nonsense)”, Orígenes declared before bending over and laughing loudly.

The agency lost the account. Good artists when in advertising may be like that. They lose the client but they still have the last laugh.

Gloria Swanson (the actress who spent large periods of time living in Sintra, where she owned a house in Almoçageme) had also almost disappeared in the transition to the ‘talkies’. Some of her words when playing Norma Desmond (the character in “Sunset Boulevard”) were bitter and seemed to trigger old ghosts: “I’m still a great star, it’s the films that have become small. In times past, cinema held the gaze of the entire world, but that was not enough, they also wanted to have the ears. So, they opened their mouths and began talking and never stopped…”.

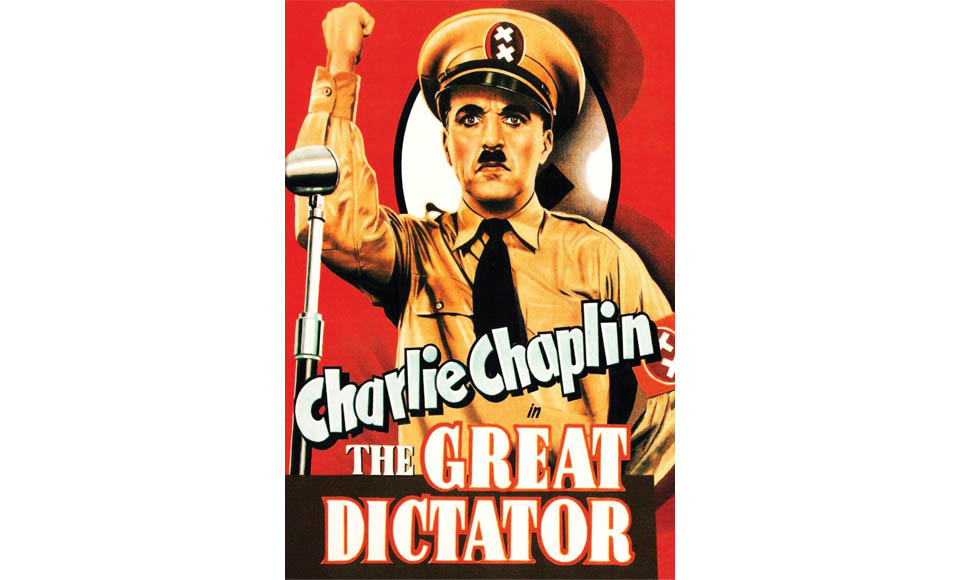

Chaplin was one of the rare cases who managed to maintain their popularity while for a long time refusing to include dialogue in his works. He produced his first film with dialogue “The Great Dictator” in 1940, already thirteen years on from the premiere of “The Jazz Singer”. At this time, he declared in an interview: – “You may say that I detest sound. It’s come to end the oldest art in the world; the art of pantomime. These films annihilate the great beauty of silence”.

It was the silence of images that the most fundamentalist defended as if: – “A poetic magic specific to cinema. The dialogue kills the poetry” – so they would say.

The studios did try and hold onto some of the most consecrated figures through running a campaign under the slogan “Listen to the stars talking”. There was footage shown before other films, sequences with dialogue featuring the most renowned faces who had hitherto remained dumb and exaggeratedly expressive in their acting. In revealing their voices, many of them would surprise the audiences, who would sometimes respond with open laughter. Almost overnight, an entire generation of the best known names in cinema would be removed from the ‘screen’. Few would survive the transition to sound, Greta Garbo, with her deep voice, was one of the few who managed this feat. For the film “Anna Christie”, MGM embarked on a major campaign with the slogan “Garbo Speaks” and her voice convinced her new publics.

The need to innovate

North American cinema in the 1920s was going through a serious crisis. Box office revenues were down drastically, the prestige of many stars had been hit by major scandals and the press was recurrently critical of the opulence and extravagance of Hollywood life.

The studios, without any apparent way out, grasped that they needed to evolve but the studio managers, always very conservative, did not seem to perceive any way past the problem. This “modern fad” for sound, while interesting, was perhaps another transient fashion as was defended by those who maintained good cinema was silent cinema. The major studios, all – or almost all – rejected this technological novelty particularly because any such option required heavy investment in establishing the technical solutions appropriate to recording and reproducing dialogues.

In the middle of 1926, news reached Hollywood that laboratory engineers at two of the largest electricity companies in the United States – Western Electric and General Electric, had finally managed to synchronise sound and image at the end of almost a decade of studies and trials.

The report caused little stir and the first approaches to the studio magnates even went badly with some signs of rejection. Only Warner Brothers decided to take the risk. One of those responsible would later confess that they only accepted the proposed solution because there were really no other alternatives. The studios were in a very difficult financial situation after several public flops and fairly expensive stars with the management prospects so gloomy that one option on the table was to declare bankruptcy and close the doors.

Among the Warner clan, not all believed in the importance of this huge step. Harry Warner voted against and is reported as saying at the meeting when the final decision was taken: “I don’t who could ever possibly be interested in hearing these actors speak”.

The initial idea was to use the sound only to convey the music, the ambience and sound effects. At the very beginning, it was not even about recording the voice.

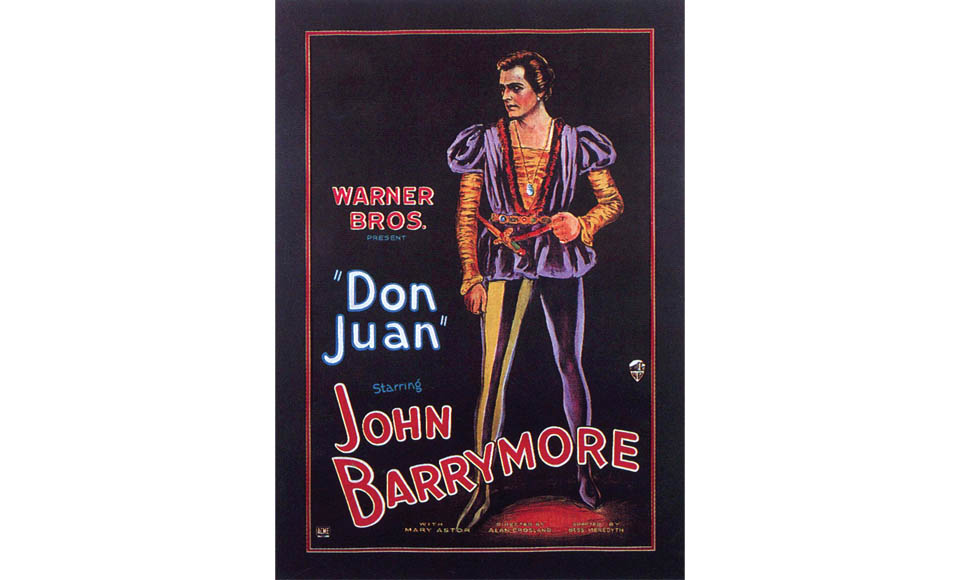

Without any alternative, the Warners took the risk cautiously and with discretion. When they were approached to try out the new system, entitled “Vitaphone”, and which was the most reliable of all those hitherto tested, they received a proposal to acquire the respective patent. They accepted, paid and took advantage to add sound to a film already in production, “Don Juan”, with John Barrymore (great-grandfather of Drew Barrymore) and Mary Astor. To hedge their bets, they made two versions, one of them without any sound.

At the premiere of the with-sound version, the music was performed live by the orchestra of the New York Philharmonic Auditorium. Thus, on 6 August 1926, at the Warner Theatre in New York, there was the official release of a film entirely with sound even while the music was this time also played live.

The reactions from critics were lukewarm but the public flocked to see this innovation. Jack Warner told newspapers at the time: “The novelty of sound cinema will not disappear. What has ended is the novelty of silent films.”

Finally, they talk!

The first official session of talking cinema took place on 27 October 1927. “The Jazz Singer” served to confirm that films had won over usage of the word. However, it remains curious that this film, cinematographically banal, is more sung than spoken. The lead actor, Al Jolson, was a renowned variety artist. Given the mass success of this film, every agent in the business was already applauding in finally understanding that they now had available the means to attract the masses to cinema screens. In turn, the established stars, naturally shocked at looming unemployment, fostered deep grudges against the talkies. Actress Clara Bow, on understanding that there was a major movement of fire engines heading towards the Universal studios, shouted to the four winds: “I only hope it’s the sound department that’s burning”.

In the early period, the objective was to make films that could make a simultaneous premiere in two versions, one silent and the other with sound because the appearance of sound had brought a problem to studios as regards their international markets. A large proportion of the turnover came from international markets and it would be complicated to impose films that were spoken in English on distributors in other countries where English was not spoken and audiences did not understand the dialogues. At the outset, the solution found by one engineer was an attempt to save some of stars of silent films: their voices would get dubbed by other actors and actresses with better vocal skills, especially for singing. Clearly, this must have caused some unease among the “owners” of the voice as they may have spoken well enough but did not charm anybody as it was not them shining on the screen but rather a species of voice double.

In 1929, two years after the premiere of “The Jazz Singer”, Hollywood was producing around 500 films and with around half featuring sound. United Artists, despite being led by the glories of the silent years, announced around this time that as from 1930 all of its productions would be spoken. There are some highly interesting comments from stars who felt they were being left behind, such as Mary Pickford, who is reported to have declared: “Putting sound on films is like putting lipstick on Milo’s Venus”. Chaplin, always radical in his relationship with sound, stated: “Cinema needs sound as much as Beethoven’s symphonies needs words”. But it was unstoppable, spoken film had arrived.

Curiously, in its earliest years, this new technique represented an unquestionable step backwards from an artistic perspective as there were a great deal of problems encountered in the recording of sound. The microphone became a hated device, a weapon that eliminated whoever did not adapt.

Based on the many behind-the-scenes stories and jokes told about these early adventures in sound, in 1953 Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen starred in one of the greatest films of all times in which the dramatic transition to sound is portrayed in the style of a musical comedy. “Singing in the Rain” allows us to understand that between the music, smiles and unforgettable choreographies, the level of suffering experienced by the stars of silent films and the depth of the hatred they nurtured for new technologies, especially microphones.

Through the plot of “Singing in the Rain”, we also grasp the difficulties with mobility that the new cinema had brought. The recording of sound was both a torment and a constant challenge for the technicians responsible. The cameras made a lot of noise while filming and so had to be closed away in sound-proofed boxes. All of these technical restrictions would hinder creativity and the adaptation took some time to occur with the new equipment necessary to lightening the load of the entire filmmaking process only arriving years later.

The studios were factories of dreams increasingly expensive to produce and involving a decent portion of risk.

This was the largest and most radical revolution in the cinema industry. It came up with new stars, redesigned the dream that sill continues evolving today ever loyal to the principle of telling a story that is emotional, amusing and that touches and enchants us.

The last film from the silent era produced in the United States premiered on 7 April 1930 and was entitled “The Poor Millionaire”. Of course, it flopped at the box office but nevertheless went down as the definitive landmark in ending an era.

Just where did they experiment with sound

In France, where cinema first started with the Cinematographic presentations of the Lumières in 1894, there were diverse attempts to ensure the means of recording sound in synchronicity with the image.

There are references to Lengaste Baron, who patented a system of devices to enable the simultaneous recording and reproduction of images and sound in Paris. Baron even produced various types of film but became disillusioned with the lack of investor interest in his idea and gave up soon after.

There was another patent attempt in 1905 for equipment with a long but indicative name: “The electric registration of sound over the image on the same film”. The inventors also eventually gave up on the idea but this was unfortunate as they were heading down the right track… when later, an awfully long time later, 22 years afterwards, this was the same principle applied by the American engineers at Western Electric to come up with the solution that would finally synchronise sound and image.

Already in 1900, the Universal Exposition in Paris was abuzz with the “Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre”, short films which showed the great stars of the Paris shows, such as Sarah Bernhardt, singing.

With greater or lesser levels of synchronicity, this combined the projector with a phonograph (great-grandfather of the record player). In France, with this same technique, various sequences of film were produced which recorded the singers of the period for all time. Music videos old fashion style…

In the summer of 1908, Leon Gaumont rented a cinema in Paris and, through various weeks, showed to great success, his film with sound through recourse to the Chronograph. Gaumont also registered this technique but as he did not gain the commercial returns he was expecting, he also fell by the wayside.

French experiences that long pre-empted the actual emergence of sound cinema but with World War One intervening to irreversibly terminate this technological evolution.

Today, the evolution of cinema has become so complex that there is not even consideration of what the lack of noise, dialogue might do to a film. The discussions today are around the purity of the sounds and images. We create surrounding soundscapes that extend beyond the understanding perceivable by our auditive sound device. When talking about the recording of sound for a film, we hear the abbreviations and brands that trigger images on just hearing them; THX, DTS, Atmos, Dolby are more than abbreviations, they ae the sound doorway to our involvement in images. 95 years ago, the technical and marketing communication challenge was as simple as getting them to talk, in itself a major achievement for those times.

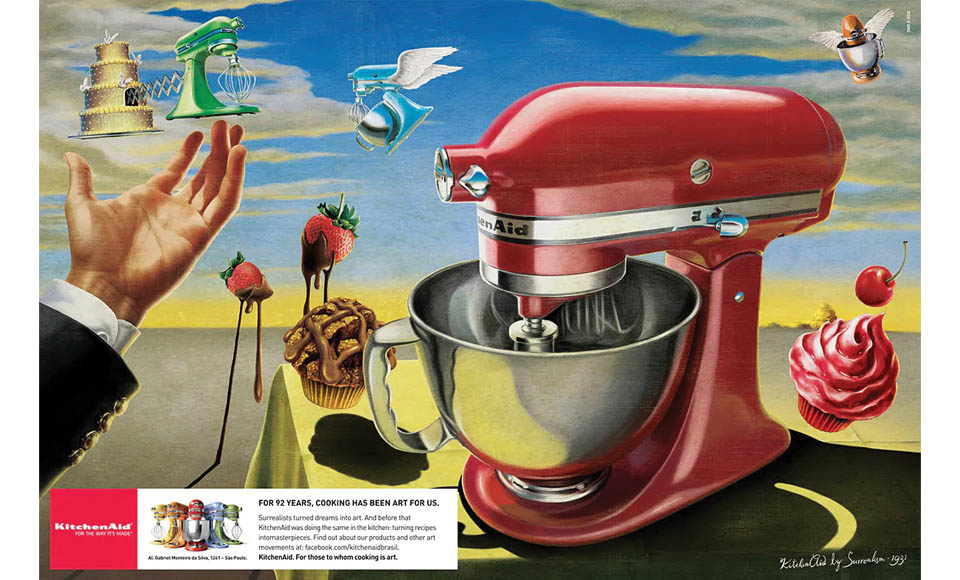

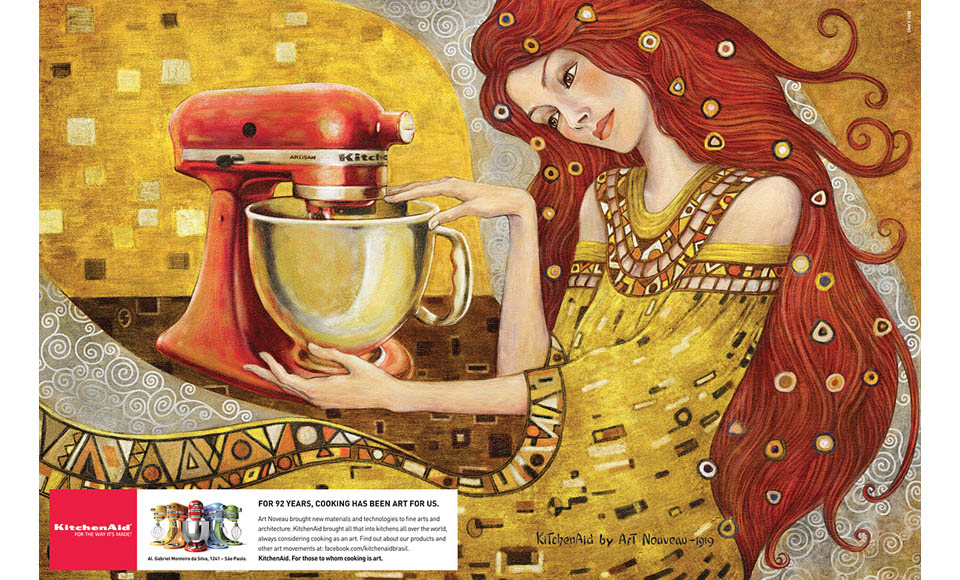

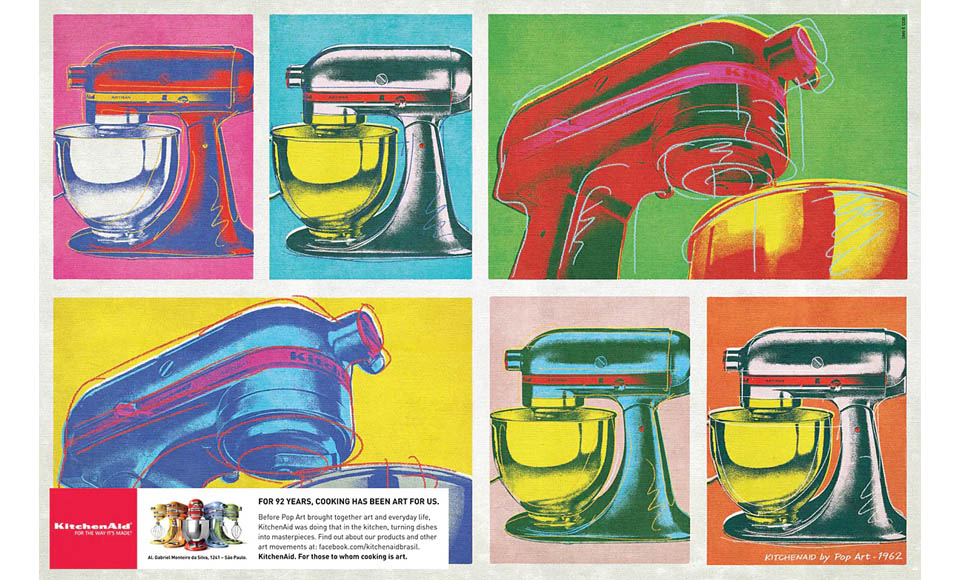

Campaign for Kitchenaid food mixers. Advertising loves to “steal” from the great artists.

When advertising imitates art that imitates life. Benetton was not content to make commercial advertising. The photographer Olivieri Toscani, responsible for the brand’s campaigns in the 1990s, was constantly stepping over the lines and making the story.

American Way of Life, the illustrator Norman Rockwell deployed his art not only for reproduction but especially for creating the ways in which Americans perceived life in the early 20th century. Much of his work was for advertising.

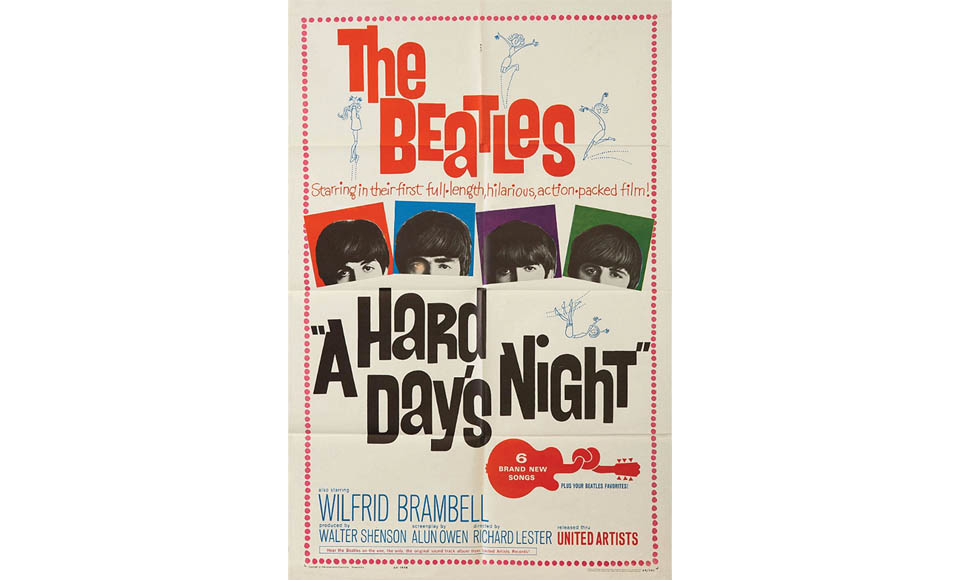

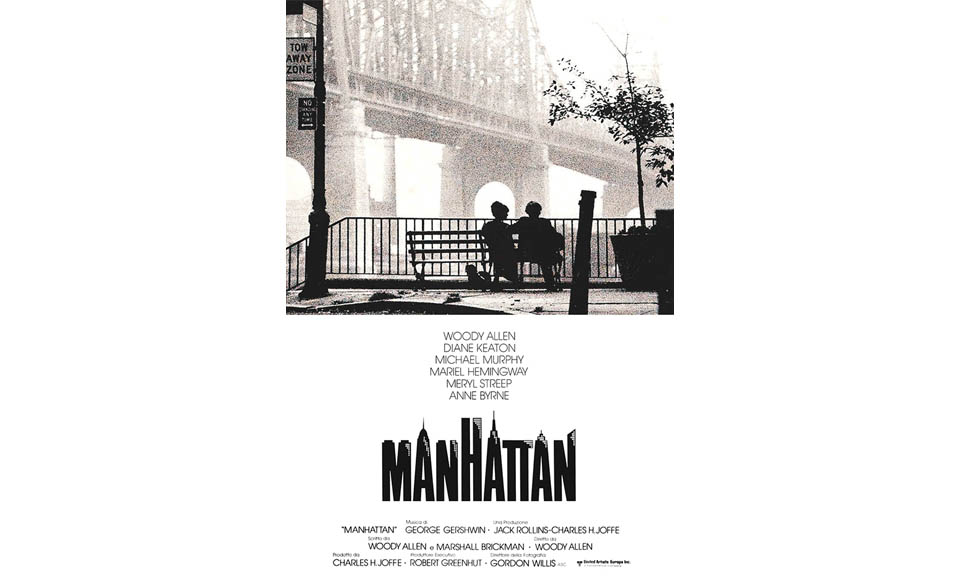

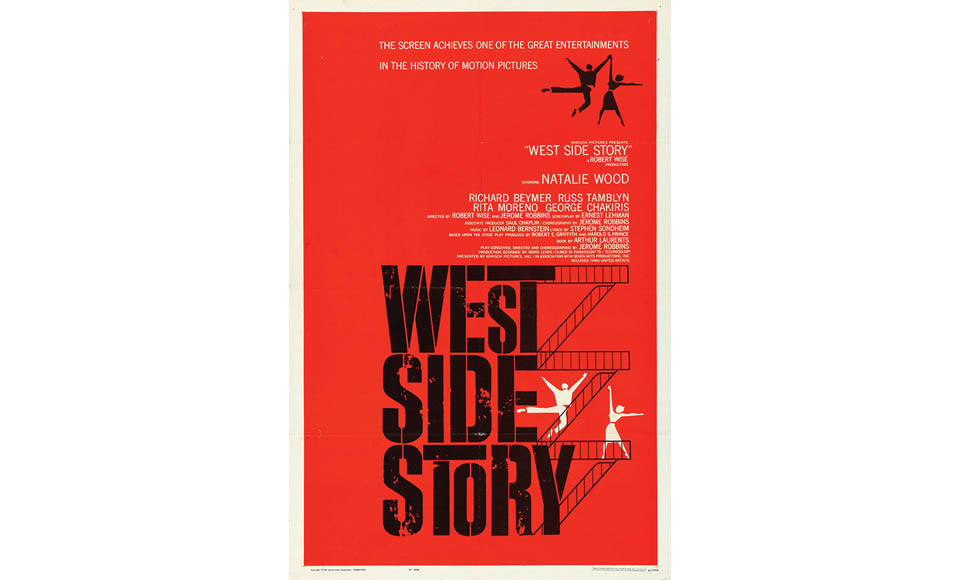

Joseph Caroff: the man of all posters. Throughout decades, Joseph designed posters for Hollywood and logos for major corporations. The grandiosity of his work contrasts with the lack of profile of his reputation.

Silk Cut Cigarettes. Was it advertising? Was it art? Was it both? This British campaign from the 1990s was defined by its artistically impeccable billboards.

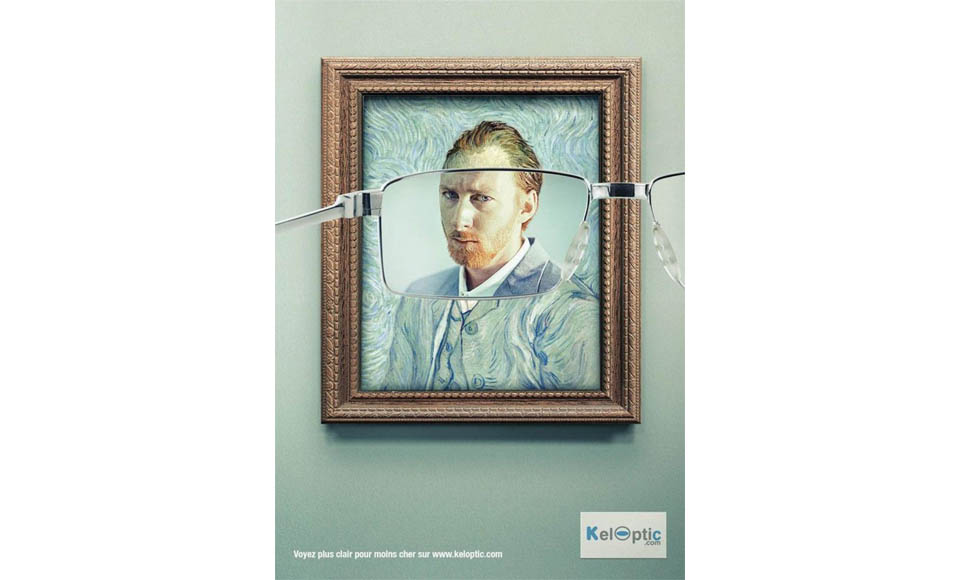

Keloptic. As a parody or as a reference, the major artists are always lending their faces for advertising. What kind of fee would Van Gogh have charged?

Lithographic posters, Jules Chéret, 1889, France. The owners of Parisian nightclubs swapped alcohol for art.