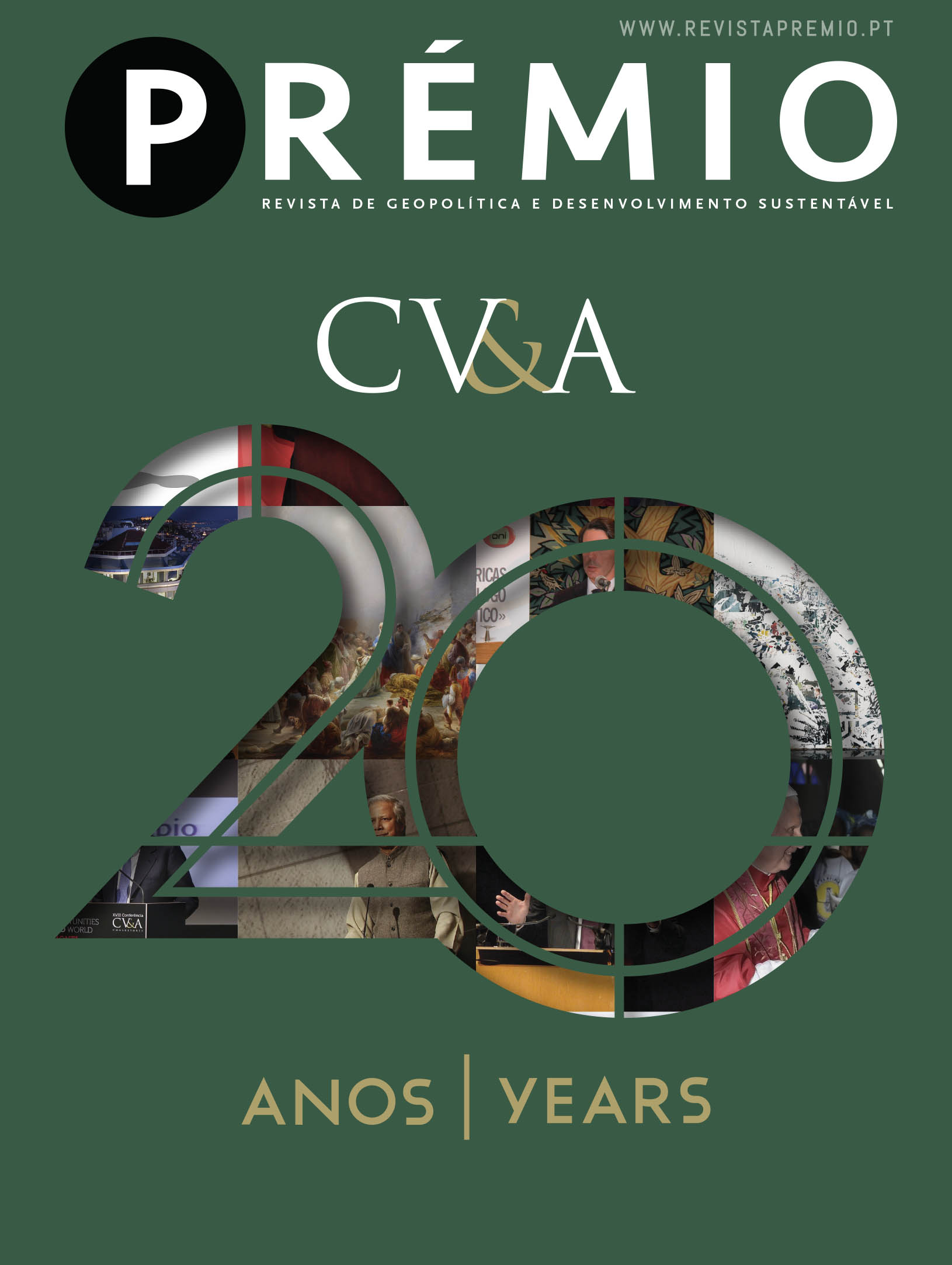

The structural problems today shaping the Portuguese reality have been on the agenda for decades. In this fairly grim scenario, we might be led to consider that nothing has changed in these last 20 years. However, taking into account the social framework, the economic dynamics, the very configuration of parliament or even our – increasingly digital – means of communication, we may grasp how our realities have undergone radical transformation. Two decades later, this is certainly “another country” while never giving up on being “the Portugal of always”.

Blandina Costa

Luís Eusébio

Words such as as “sustainability”, “e-mobility”, “artificial intelligence” or abbreviations such as “ESG” and “LGBTQIA+” convey the differences of the contemporary world to that prevailing in 2003. At the time, we were already doing our sums in euros but still taking our first steps into the universe of the Internet. Today, we live on social networks, we listen to music on digital platforms, we purchase online and have mobile apps to pay our expenses. We are all fitted out with the world of opportunities put forward by our smartphones and smartwatches. We are ever more enthusiastic about electric cars and hundreds of cycle paths have popped up across the country.

From a more closed and conservative world, we entered a scenario in which same-sex marriages happen, abortion is legal through to 10 weeks and the debate around euthanasia is ongoing. We accompany the trends that are shaping the world in a pyramid of power that is progressively placing China at the top, in a global balance that is notoriously tilting towards Asia. The dependence of Europe and the United States on Asian factories which produce many of the chips and semiconductors to be incorporated into our cars and equipment.

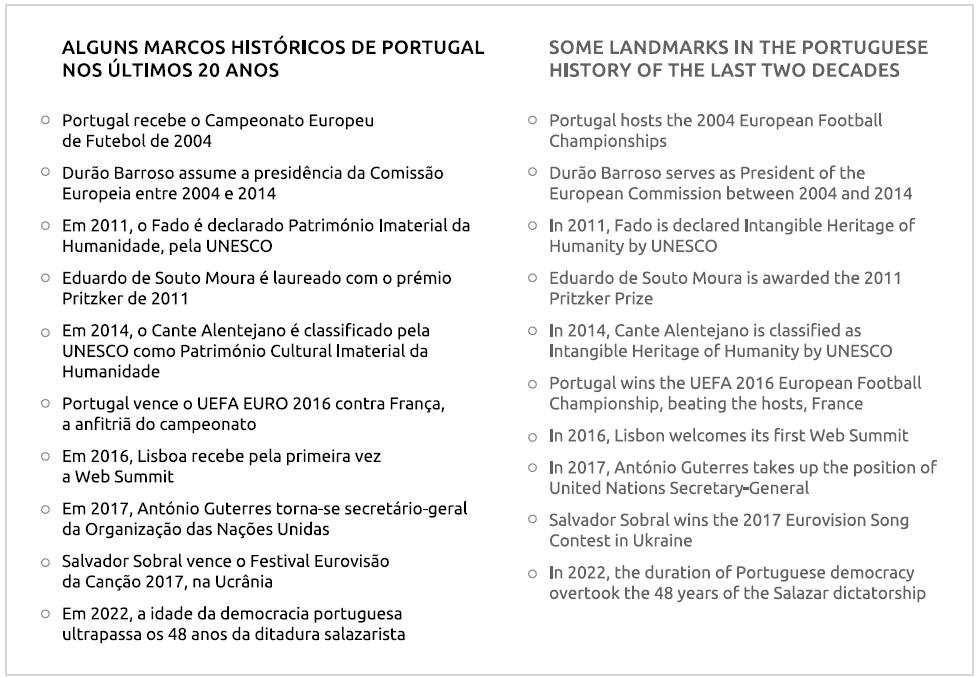

The very European Union changed, reconfigured in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The greatest enlargement in its history took place in 2004 with a total of 10 new states joining, followed by another three arrivals in 2007 and 2013. However, with Brexit, this Europe of 28 became one fewer with the departure of the United Kingdom in 2020. These profound changes are still ongoing: the death of Queen Elisabeth II, an unquestionable symbol of stability throughout over 75 years, gave way to a new era. In 2023, King Charles III was coronated in the same year as commemorations of the 650th anniversary of the oldest diplomatic alliance in the world and reaffirming bilateral relationships between Portugal and the United Kingdom.

We have changed a lot, nevertheless, now — just like twenty years ago —, we remain familiarised with two words: “crisis” and “war”. From a crisis resulting from the dot-com bubble, we arrived at the pandemic and energy crises having passed through the international financial crisis along the way. From war in Iraq, in the aftermath of the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers in New York, we now contemplate war at the entrance to Europe following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Portugal was not only no stranger to these events but faced multiple (and repeated) obstacles. In 2003, the country “was flat broke”, as the recently appointed social democratic prime minister, Durão Barroso, said in reference to the prevailing economic recession. Today, we are dealing with an inflationary crisis trailing in the wake of a public health crisis and always accompanied by an alarming environmental crisis that would seem to be endless in scope.

In this context, the political and social turbulence is visible. There are successive strikes by teachers, doctors, nurses or young activists, for example, in a country where the young people are only able to perceive dignified futures beyond the national borders. The concerning emergence of a radical and populist right-wing reflects the discontent of a population who are heavily burdened by the rise in the cost of living, driven both by inflation and the interest rate hikes.

However, when all is said and done, have we become richer or poorer? Do we live better or worse than in 2003? What is the relationship between the economic and political cycles?

After so many tremors how robust is the Portuguese economy?

A close look at the trend in the GDP growth rate displays the difficulties the country has experienced over these last two decades. In this period, there were six years of recession. We only obtained growth rates of above 3% — the average value registered over the 1900s — in three years.

From the sovereign debt crisis to the pandemic crisis, with an international bailout along the way

We started out in the 21st century with an economic crisis born out of the bursting of the dot-com bubble that had grown around the technologies and the advent of the Internet. This was followed by a stock market slump that sent ripples through the global economy in the following years. Portugal did not escape contagion. In 2003, the country was already tasting the bitterness of recession.

Certainly fresher in the memories of the Portuguese is the crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the worst years of recession had happened earlier in the wake of the international financial crisis — sparked by the spectacular implosion of the American Lehman Brothers bank in 2008 in what became known as the subprime crisis. In turn, this led Portugal to follow in the steps of Greece and, in 2011, to request an international bailout from the Troika — the combination of the IMF, the European Central Bank and the European Commission — for a total amount of 78 billion euros.

The recession was one of the two longest in Portuguese economic history, taking into account the time required for GDP to recover to the previously existing level: beginning in 2009 (in the midst of the world financial crisis) and ending only in 2018 (when GDP again exceeded the 2008 level).

How did the main national economic indicators and the position of Portugal in Europe evolve?

At the end of two decades (and multiple crises), the country was left relatively poorer in comparison with its European peers. At the beginning of the 21st century, the GDP per capita stood at 85% of the European average. Through to 2022, this average had fallen back to 77%, according to some preliminary estimates, thus level par with Romania that, in 2000, had a per capita GDP rate only a third of the Portuguese. Only five EU member states are today poorer than Portugal: Latvia, Croatia, Greece, Slovakia and Bulgaria.

In summary, in 2003, each Portuguese citizens produced wealth of 17,253.10 euros (GDP per capita at constant prices), a broadly similar figure to the 18,949.50 euros registered in 2021 (latest figures available).

The Bank of Portugal did the maths: between 2000 and 2020, average annual growth in real GDP per capita was only 0.3%. The years of the COVID-19 pandemic contributed strongly towards this poor figure. However, even when excluding them, average growth stood at 0.8% — a figure far distant to the annual average growth rate over the second half of the last century (3.9%).

Even with this fairly insignificant growth, this does not mean everything is equal. After analysing the different sectors of activity in greater detail and their respective contributions to the production of wealth, the former Economy Minister, Pedro Siza Vieira, described how the profile of the Portuguese economy has changed. The weightings of construction and property declined in conjunction with financial services. On the other hand, tourism and the information and communication technologies have gained in importance. Industry grew on the back of exports, which attained a weighting of 50% in national GDP. In contrast, we may report that in 2003, sales to the exterior accounted for only around 28%.

Examining the specific case, our economic dependence on tourism has intensified. The contribution of this sector to national GDP grew from 4.5% in 2003 to 10.9% in 2022.

Even demonstrating promising signals, in order to get the economy growing, it is essential to cut the level of debt, whether of the public or the private sector, especially in a period of rising interest rates.

The rocky path of the public coffers

In the wake of the sovereign debt crisis that led Portugal to request an international bailout in 2011, public debt peaked at 132.9% of GDP in 2014. With Portugal emerging from the international financial bailout within the defined period of four years, it did prove possible to make significant progress in cutting the debt ratio that in 2019 had already fallen back to 116.6% of GDP. In this year, Portugal commemorated another feat in the public accounts with the state registering its first budgetary surplus in the history of Portuguese democracy: 0.1% of GDP.

The Minister of Finance at the time, Mário Centeno, attributed this to the dynamics of the economy and the labour market that drove rising fiscal revenues and company contributions to the social security system. In fact, the country was able to drive down the unemployment rate from a historical peak of 17.1% in 2013 to less than a half. In 2022, this rate came in at 6.5%.

Portugal benefitted from the accommodative monetary policy (quantitative easing) in effect at the European Central Bank through to mid-2022, which benefitted the national financial position as the ECB president stated in 2016 when appearing before MEPs: “The reductions in the ECB interest rate are to a large extend benefiting the vulnerable Eurozone countries and the fragmentation of financing costs and loan conditions in the different countries has decreased.”

The trajectory in the public coffers and the national economy appeared to be set for a rosy future, however, the COVID-19 pandemic brought an end to such prospects. The debt to GDP ratio once gain shot up to a historical maximum of 134.9% of GDP in 2020. In turn, the state registered a very significant budget deficit at 5.8% of GDP.

Following this fall, the Portuguese economy is already displaying signs of recovery in 2023. The public GDP debt ratio dropped back to 113.9% in 2022 and, recently, the International Monetary Fund more than doubled its growth forecast for Portugal (up from 1% to 2.6%).

Shall we be able to harness these favourable winds and stabilise the direction of the country and counter the idea (confirmed over the last two decades) that Portugal is condemned to bring up the rear in Europe?

In addition to crises, the structural motives for the “mediocre” national ranking

A study by SEDES on the economic development of Portugal, which analyses the first decades of the 21st century attributes the grade of “mediocre” to national evolution and pointing to structural factors explaining the lack of growth: “In the last twenty years, the country has demonstrated its inability to accumulate capital and stimulate growth in the “labour” factor of productivity. Since 2000, Portugal has registered low levels investment, with reduced or negative marginal efficiency of the invested capital over a 10-year period, and potential output per capita in Portugal does not amount to more than 35% of the level of Luxembourg or 41% of Ireland.

For the country to experience rising standards of living, there is the need to boost the productivity of the “labour” factor. However, this simply has not happened according to the SEDES study. Simultaneously, Portugal needs to attract quality, which, in turn, requires the incorporation of knowledge and technology into production.

To this context we have to add the high level of taxation weighing on the Portuguese. The 2022 statistics, released by the INE, report a fiscal burden coming in at 36.4% of GDP. While this ranks below the EU-27 average (40.5% in 2021), this represents the highest national taxation rate since there were records.

Approaching the period since the beginning of the 21st century, in their work that translates as “Crisis and Castigation: The imbalances and the bailout of the Portuguese economy”, Fernando Alexandre, Luís Aguiar-Conraria and Pedro Bação apply the expression “long stagnation”, highlighting that this weak growth “is the most serious structural problem of the Portuguese economy”.

Without resolving these structural problems, the country remains extremely exposed to external interference and shocks — as verified with the pandemic in 2020 and the Russian war against Ukraine triggered by invasion in 2022 and with no end in sight.

The difficulties experienced by the Portuguese reflect in various different indicators, including the risk of poverty and levels of indebtedness. Despite the risk of poverty rate — the proportion of inhabitants with net income (per equivalent adult) of below 6,608 euros (551 euros per month) — having fallen from 20.4% in 2003 to 16.4%, in 2021, the impact of the pandemic on the standards of living and earnings of the Portuguese population was intense as detailed in the report “Poverty and social exclusion in Portugal”, published by the National Observatory for the Campaign against Poverty in 2022.

This study also conveys how there has been a sharp increase in social inequalities. Indeed, Portugal features as the EU member states with the largest increase in levels of income inequality, relative to the previous survey (not covering Slovakia).

Taking the last twenty years, the growth in average employee remunerations in real terms advanced 6.8% between 2000 and 2010, and 3.1%, from then onwards. This was progress, certainly, but this falls far short of the period between 1990 and 2000 when earnings surged 37.8%. In 2022, the gross total monthly level of employee remuneration stood at 1,411 euros, which represents an increase of 3.6% in nominal terms and a fall of 4.0% in real terms.

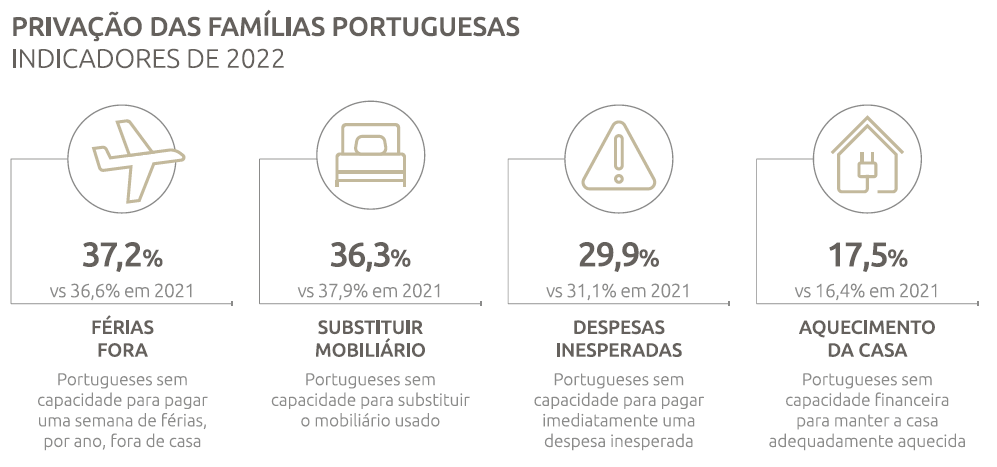

The pandemic, allied to inflation and the rise in interest rates, penalised household income. The effects of the rise in prices on the conditions of families reflect in the worsening situation of material and social deprivation, as ISEG professor, Carlos Farinha, highlighted in an article on poverty and inequality.

Between the politics around the causes and the cases, what is left of the credibility of the system?

The life of the Portuguese is still more difficult and successive governments have not been able to appropriately respond to the country’s structural problems. The Economics Professor, Abel Mateus, explains that the quality of democracy displays serious failings, perceived by citizens as “deficient”. This perception extends to the institutions of government, on to parliament and especially the political parties.

The data effectively conveys the degradation in the quality of Portuguese democracy. The “Democracy Index” produced by the Economist Intelligence Unit reflects this fact: in 2006 (the first year of publication for this indicator), Portugal took 19th position in the ranking, with a global evaluation of 8.16. Currently, according to the 2022 ranking, Portugal has dropped back to 28th place with a score of 7.95. Portugal no longer belongs to the group of “complete democracies”, falling back into the group of “democracies with failings” due to the shallow political culture, low levels of participation in political life and problems relating to the functioning of governance.

The reconfiguration of the party panorama and the re-appearance of discourses of hate

Discontent, the Portuguese point the finger at the political class unable to resolve their problems and compounding them by the incidence of corruption and bad public management. Among such cases, there was the episode, unprecedented in Portugal, of the arrest of a former prime minister. José Sócrates was taken into custody on 21 November 2014 within the scope of an investigation into suspicions of qualified fiscal fraud, corruption and money laundering. Despite having spent almost 10 months in custody, the former prime minister has yet to stand trial with the proceedings dragging on and now on the verge of expiry, only deepening the lack of faith in the system.

While, on the one hand, the reaction of the Portuguese comes with their alienation from political participation, with a surge in election abstention rates (rising from 38.4% in the general elections of 2002 to 48.6% in the most recent national parliamentary elections), on the other hand, voters have opted for small parties hitherto on the fringes. For example, in the Parliament of 2002, there were five parties with representation. In the current parliament, there are nine parties. The CDS-PP may be missing in action but the PS, PSD, PCP and Bloco de Esquerda have been joined by the right-wing Chega, Iniciativa Liberal, the pro-animal rights PAN and Livre parties.

Simultaneously, Portuguese democracy has encountered obstacles similar to those cropping up in Europe and the United States, emphasised Abel Mateus before mentioning “(…) the phenomenon of populism (…), the polarisation and radicalism induced by the large digital platforms and the lack of quality of the governing elites”.

The success of Chega, led by André Ventura, reveals a clear example of populism, leveraged by hate speech, that has also afflicted Portugal. Launched in 2019, in four years, the party has surged to become the third largest political party in the Portuguese parliament, winning over followers in segments of a population facing various challenges and not only economic but also social, beginning with the demographics prevailing.

Society: older, more digital, more tolerant and more vulnerable

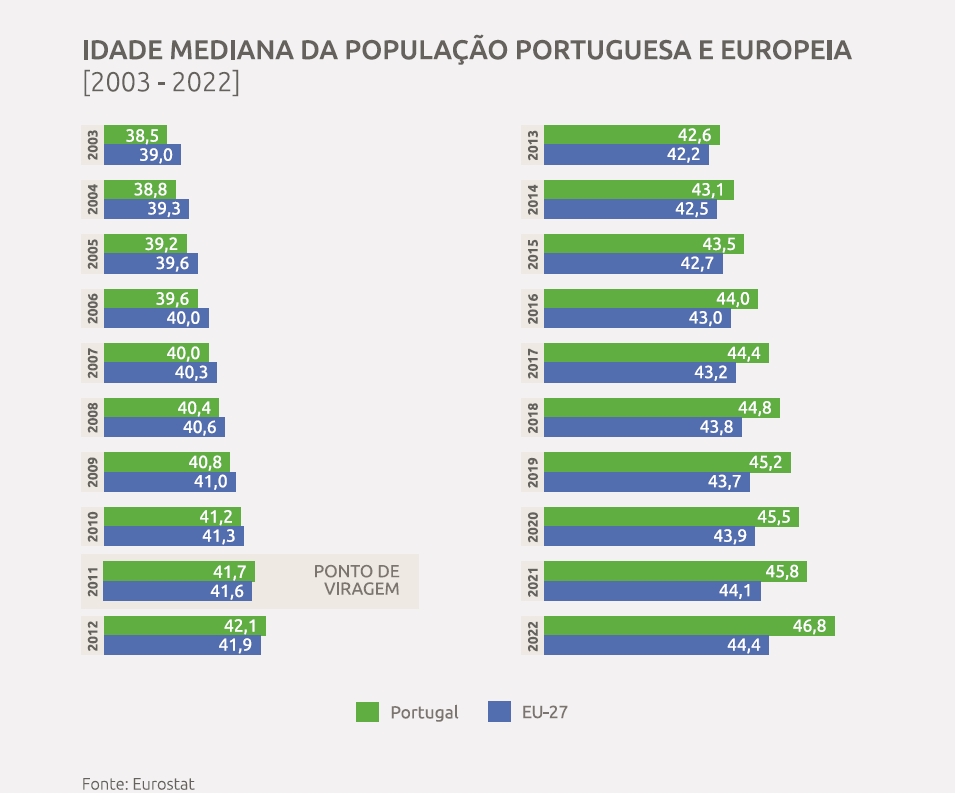

The Eurostat figures, updated in February 2023, are expressive: the Portuguese population is that which, out of the group of 27 EU member states, is ageing at the fastest pace.

This demographic phenomenon, courtesy of a reduction in the birth rate and the increase in the average lifespan, is taking place across Europe to a greater or lesser extent and is nothing new. Irrespective, while, in 2003, the average age of the Portuguese population was 38.5 years, in 2022, the scenario was substantially different. The Portuguese are now aged an average of 46.8 years — higher than the pan-EU average of 44.4 years of age.

Given such data, the President of the Republic, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, considered this issue decisive to the future: “Do we want a Europe that recovers economically, we want a Europe that is socially just, that provides opportunities for young people? The answer relates to the demographics”, he declared.

Compounding this problem is the trend in youth emigration. In recent years, we have witnessed a veritable national brain-drain. In 2003, according to INE data, the majority of Portuguese emigrants held only primary school education (77.4%), only 9% had completed Secondary/Higher education qualifications. According to the 2021 Census, the Portuguese emigration profile is now significantly different: 47.6% hold a higher education degree.

In fact, there are countless challenges arising from this demographic position, the significant rise in pressure on the social security system, the urgency of strengthening the response capacity of the national health service and extending to combating loneliness and isolation among the elderly population.

However, on the one hand, while Portugal appears to be steadily ageing with only a slight reduction in the active population, on the other hand, the national society and economy has never been quite as dynamic and open to the world. The unavoidable process of digitalisation that the country has embarked on may represent one of the key drivers of this openness.

From the launch of Facebook through to the era of artificial intelligence

We today live with an increasingly large percentage of our time spent online. The advance of the digital universe in Portugal has become determinant to national evolution over the course of the last 20 years. After all, the Internet has radically transformed the ways in which we interact, dialogue, work, study, access content, go shopping, close deals and take decisions.

Again according to INE data, in 2003 — one year prior to the appearance of Facebook, the social network that swept the world —, only 11.3% of the micro, small, medium or large Portuguese companies maintained an online presence. In 2021, that level was 40.1%.

Similarly, according to ANACOM, 88.2% of households had an Internet connection in 2022. This percentage corroborates with the growth in the numbers signing up to Internet services in Portugal over the last twenty years.

In this context, we should highlight the overwhelming weighting of the social networks in our daily lives. According to a Marktest study The Portuguese and the Social Networks, published in 2022, 63% of the population use social networks. Each of these users run around six different accounts across the various platforms.

In turn, Data Reportal affirms, in its Digital 2023: Portugal report, that Portuguese citizens dedicate an average of 2.25 hours per day to their social networks. They maintain that 92.2% of national Internet users hold an account with at least one social network.

However, almost 20 years on from the launch of Facebook, these spaces of interaction, omnipresent in the lives of the Portuguese, shall also undergo a radical transformation that shall leave the future of these ecosystems in question. An article entitled “The Future of Social Media Is a Lot Less Social”, published in The New York Times, defends that:

In parallel, the digital technology world is facing the mushrooming of a set of platforms revolutionary both for society and the economy.

2023 saw the newspapers lead with headlines that, twenty years ago, would rarely have surged outside of science fiction. At the end of 2022, the appearance of ChatGPT, an Artificial Intelligence (AI) generative language model impacted on the global agenda in keeping with its surprising capacities to simulate, with naturalness and fluidity, human communication.

The world in your pocket, a borderless pandemic and mental health emerging from the shadows

The connectivity that the country built up over the last two decades proved determinant in navigating the global crisis that erupted in early 2020: the COVID-19 pandemic. After all, these digital tools enabled countless sectors of social and economic life to continue functioning, even while new challenges and shortcomings also emerged.

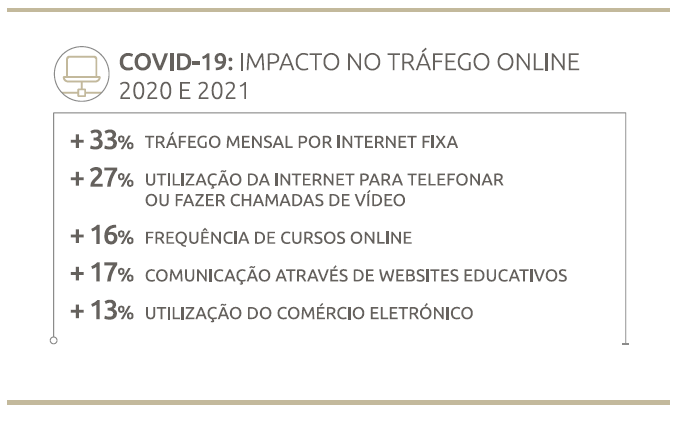

Consequently, the periods of confinement resulting from this pandemic brought about a significant rise in electronic communications. The recourse to information technologies opened the doors to remote working: a working dimension that looks to have arrived to stay, and today enabling new ways of working that encourage digital nomadism and migration to inland areas.

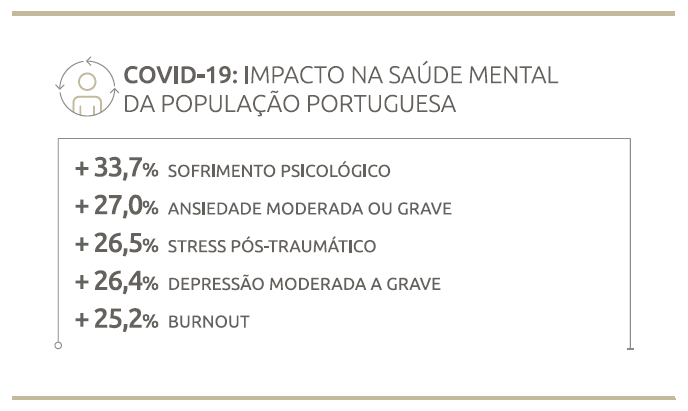

Despite the connectivity built up by the digital platforms, the pandemic led to a vast set of invisible consequences to the mental health of the population. Given this scenario, the SNS – the Portuguese National Health Service, highlights the impact of social distancing, isolation, fear and uncertainty in relation to the future and the loss of earnings to the wellbeing of the Portuguese.

Almost a half of Portuguese adults (47%) affirm that, according to the STADA Health Report 2022, their levels of stress worsened at the beginning of the pandemic. Indeed, while the theme of mental health had already gained some space over the course of the last two decades, the pandemic converted it into a truly unavoidable issue.

The numbers published by the SNS also help in grasping the extent of this issue:

Twenty years ago, terms such as “anxiety”, “depression” or “burnout”, for example, appeared with far less frequency across the national social, media and political contexts. Nevertheless, today, mental health constitutes a core concern to our life in society.

From combating bullying in schools to the implementation of labour policies capable of curbing the incidence of burnout, as well as the struggle against harassment and loneliness in the elderly population, multiple problems associated with mental health have shot up the list of national political-social priorities.

For example, eco-anxiety — characterised by specialists as “fear related to the negative consequences of the climate crisis” — reflects a trauma with growing incidence among younger persons. After all, the ecological issue represents the great driver of the political involvement of the younger generation, who perceive themselves ever less in the conventional party political forums.

These young Portuguese, who will be taking the helm of the country over the next couple of decades, have brought new themes and new priorities to the public debate: combating racism and the demands for equality whether on behalf of feminism or the LGBTQIA+ community, as well as animal rights and the struggle for climate justice. This is clearly a distinctly radical agenda when compared with the issues dominating the news back in 2003.

In these last two decades, we have broken new frontiers but also promises. The country suffered and was transfigured by the crises buffeting the economy over these cycles. Furthermore, the future of the economy and politics still seem shackled by the persisting structural problems. The next twenty years shall certainly raise a series of challenges: from the climate crisis to the threat to democracies and taking in the impact of the now emerging deep digital transformations.

After all, what vision does Portugal hold for the future? What position should the country take within this framework? And in two decades time, will we really be so different?