António Mateus, Journalist

DAY 1

– “Zhurnalisty! (journalists)

– “Portuhalʹsʹki zhurnalisty (Portuguese journalists).

Alex explains who we are to the Ukrainian military peering into the car after having already requested identification documents – both personal and for the vehicle – as they ask where we are heading.

– “Bashtanka”! (the name of the location, situated between Mykolaiev, the buffer city against the Russian advance on the southern front, and Kherson, already occupied by the invading forces) explains our driver and causing a mini-conference among the soldiers and police who were manning the checkpoint with their Kalashnikovs drawn, the umpteenth we’d encountered since leaving Odessa over two hours earlier.

The response drew the attention of an officer.

– “Ziydy z dorohy! Potyahnutysya do krayu!” (Get off the road! Pull up by the kerb!) – the officer ordered, pointing to a queue that already contained various other vehicles and their assorted occupants.

Then, on hearing that I and Rodrigo Lobo (the RTP cameraman with whom I was dispatched to southern Ukraine) were Portuguese journalists, he asked for our passports and then the credential issued by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence, which were photographed on his smartphone and sent off for verification by the state security services.

Patience. In large quantities. One of the many requirements for working as a journalist in a warzone. And particularly so in this case given how the suspicions of the military, police and secret services had multiplied in keeping with evidence of infiltration by spies and informers identifying targets for Russian artillery strikes.

-“Bez vyshchoho dozvolu ne mozhna khodyty na Bashtanka! Ts’oho razu tse zona boyovykh diy!” (Without higher authorisation, you cannot go to Bashtanka. At this moment, it’s a warzone!”) – the officer stated. Alex tried to argue that we had been authorised by the spokesperson of the Ukrainian armed forces in Mykolaiev, Lieutenant-colonel Dmytro Pletenchuk, to visit the recently bombed town but this did little to appease the officer’s mistrust.

Our ‘fixer’, Maria Gorbunova, stepped into action and called Dmytro and, when he answered, told him about the situation we were stuck in. She put him on the phone talking to the checkpoint officer and the thick-set expression on his face was giving way to the faint outline of a smile in less than a minute.

-“ Mozhe sliduvaty. Vse harazd!” (You can go. It’s all ok!) – he gestured to Alex, while indicating to the soldier to move away from the front of the car.

Back on the road but with an added concern. The half-hour lost at this checkpoint had already eaten in to the margin available for the report, from close proximity to the front lines, as there was still the need to do over 200 kilometres in the opposite direction, get back to Odessa before the curfew and edit the report for the Telejornal (RTP1) evening news broadcast for which it would still need subtitling.

However, after the decades of journalism already experienced (39 years), a third of which spent in complicated scenarios, I return my focus to where it should be, particularly at such times; attentive to the not always obvious signs of danger.

Alex pushes on the motor of his Daewoo Nexia. The 107 horse-power seem to be in top form despite the ten years of the vehicle accelerating its way along the twisting road running between fertile agricultural lands, the natural wealth of one of Europe’s largest cereal producers.

The road divides at the site of yet another checkpoint. Behind the sandbags protecting the military unit, there stands the road sign, left to Bashtanka, and straight on to Kherson and, by the side of this junction, a few dozen metres from the checkpoint, the remains of two military vehicles.

Once again, the same questions, the same checks, the same patience. When insecurity becomes routine. Now, deepened by the proximity to the frontline of combat. Loosening the bulletproof jacket to “fish” for my journalist credentials was a gesture that attracted the looks of two soldiers who, with tired looks, stood guard over the intruders.

– “Vse dobre!” (It’s all okay!)

We turn left, crossing a short bridge and coming across the first sign of the impact of Russian artillery; in front of us stood a burned-out ruin that had, until a few days ago, housed a pharmacy, the “Аптека АНЦ (with only the letters “A” and “H” still surviving) but what drew my attention was the figure, flanked by a colourful mosaic, of an astronaut alongside a rocket.

I approach from the left side of the building and finally understand the reason that figure seemed familiar to me; it’s a depiction of Yuri Gagarin, the Soviet cosmonaut who became the first human to travel in space in 1961 (an area that has fascinated me ever since I was a young lad).

The twists that life has; the Russian missile destroyed a façade paying honour to the man who sixty years earlier had placed Moscow in the lead in the space race at the height of the Cold War. With the same “blindness” applied to the other projectiles that hit the Bashtanka hospital in the same mid-afternoon bombardment.

– “There was an operation taking place when the explosion happened. The shockwave blew out the windows and doors of this entire ward. Thankfully there were no deaths. The operation was to amputate the hand of a civilian” – describes Alena Vasilievna, the hospital clinical director.

On the operating table, there was a civilian who had been wounded days earlier by Russian artillery fire. Only by chance had there been no fatalities;

– “During the war, this clinic is open until 3pm… the explosion took place after 3pm” – the doctor explained, pointing to the building with its corner left in ruins by the shelling. “If that had happened earlier, with the clinic open for appointments, there’d have been a massacre”.

The force of the explosion is clear throughout the building’s structure, the last hospital located before the frontline. The operating block, located in another wing, escaped the bombing but the appointment rooms for the radiology department were destroyed in an increasingly frequent situation caused by a strategy that does not even exclude targeting the emergency services.

The witness account comes from Svitlana Sokol, the senior hospital paramedic who described the most recent incidents experienced by her team when one of the ambulances got hit while tending to victims from a previous attack in a nearby rural zone:

“We were leaving Bashtanka when there was another bombardment”, she explained. “We came across an entire family with wounds… children, including a one-year old baby. And even animals hit by shrapnel. The ambulance itself also got hit”.

Next to the paramedic, the end of a twisted red metal sheet jutted out from among the blocks of pulverised cement. This was the remains of the door to the boiler room hit by the missile. Rodrigo and I climbed some stairs at the back and looked out over the effects of the impact and explosion of the missile.

Particularly shocking was the scenario awaiting in the room signposted as for mammography scans; the radiology machinery destroyed, projected against a wall along with the remains of window frames, ripped out by the blast, the flooring covered with shards of glass and the remains of various things and through which we made our way carefully.

Present, in my recent memory – days before travelling to the Ukraine – the vehement protests of the Russian ambassador to the United Nations Security Council, Vassiy Nebenzia, when confronted with evidence just like that which we witnessed ourselves in the terrain. A position seconded by the spokesperson of the Russian Foreign Ministry, Maria Zakharova; “Of course this is all lies!” – she guaranteed in Moscow about events taking place thousands of kilometres away.

We leave the hospital and return to the centre of Bashtanka. We stop next to a supermarket with the windows boarded up and reinforced by sandbags. The bulletproof vests clearly labelled with “Press” attract the attention of a military patrol who approach us with their AK-47s out. Once again, we get asked for our credentials and our passports that are again photographed by smartphone for verification at the “other end of the line”. They stayed there, surrounding us, until receiving the green light to let us move on; in the meantime making us the centre of suspicious looks from passers-by.

One of them came out of the supermarket – when we’d already been released from our temporary detention – and agreed to talk on camera to RTP; while awaiting the signal from Rodrigo Lobo to begin the interview, I hear “rosiysʹkoho telebachennya”! (Russian television!). I didn’t immediately get it but it sounded something about Russian and was stated in a hostile tone. I ask Alex what the people are saying and he translates. He warns me that they are confusing the RTP abbreviation with that of a Russian television station and right in a location under bombardment.

Our driver then swiftly explains to them that we are Portuguese. From a Portuguese T.V. station. And the agitation that had been building up fast disappeared as quickly as it’d begun. However, the warning was made; that microphone “cube” is unadvisable in zones under Russian occupation.

“The risk of getting taken out by a sniper or some other “bad luck” by somebody desperate at all the atrocities the Russians are doing to our civilians” – a Ukrainian soldier warns us after the initial hostility dissipated into warmth.

I again engage in conversation with our potential interviewee. However, I have to wait for the precious help of our ‘fixer’, who was meanwhile attempting to calm the owner of the supermarket who was determined to get us far away from her establishment.

– “She’s telling me that we put her store in danger if we film here! That the Russians might bomb the supermarket as they’ve already done to other places in Bashtanka!” – Maria explained to me.

– “I told her please, we’ll be leaving immediately! It’s just to interview this gentleman….” – in response while approaching the middle-aged man who’d begun to tie his bags of shopping with hooks and elastics to the back of his motorbike, which was in a very praiseworthy state of maintenance.

I explained to him that I shared his passion for motorbikes as my maternal grandfather would ride one to travel to a distant land called the Alentejo. He smiled at the sound of the name. Having broken the silence and in exchange for me presenting myself as António, backed up by extending my hand, he offered me his and told me he was called Yaroslav. Yaroslav Michailov, resident in Bashtanka.

We chatted awhile without recording and for another while on-the-record. I recall his words, just before we got back onto the road and away from all that tension:

“Nobody could think that this would happen. But despite that, this was predictable. This story began in 2014… and continued bit by bit but we thought it would just pass by”.

Far from this, the war has become a daily routine.

Alex, our driver in southern Ukraine

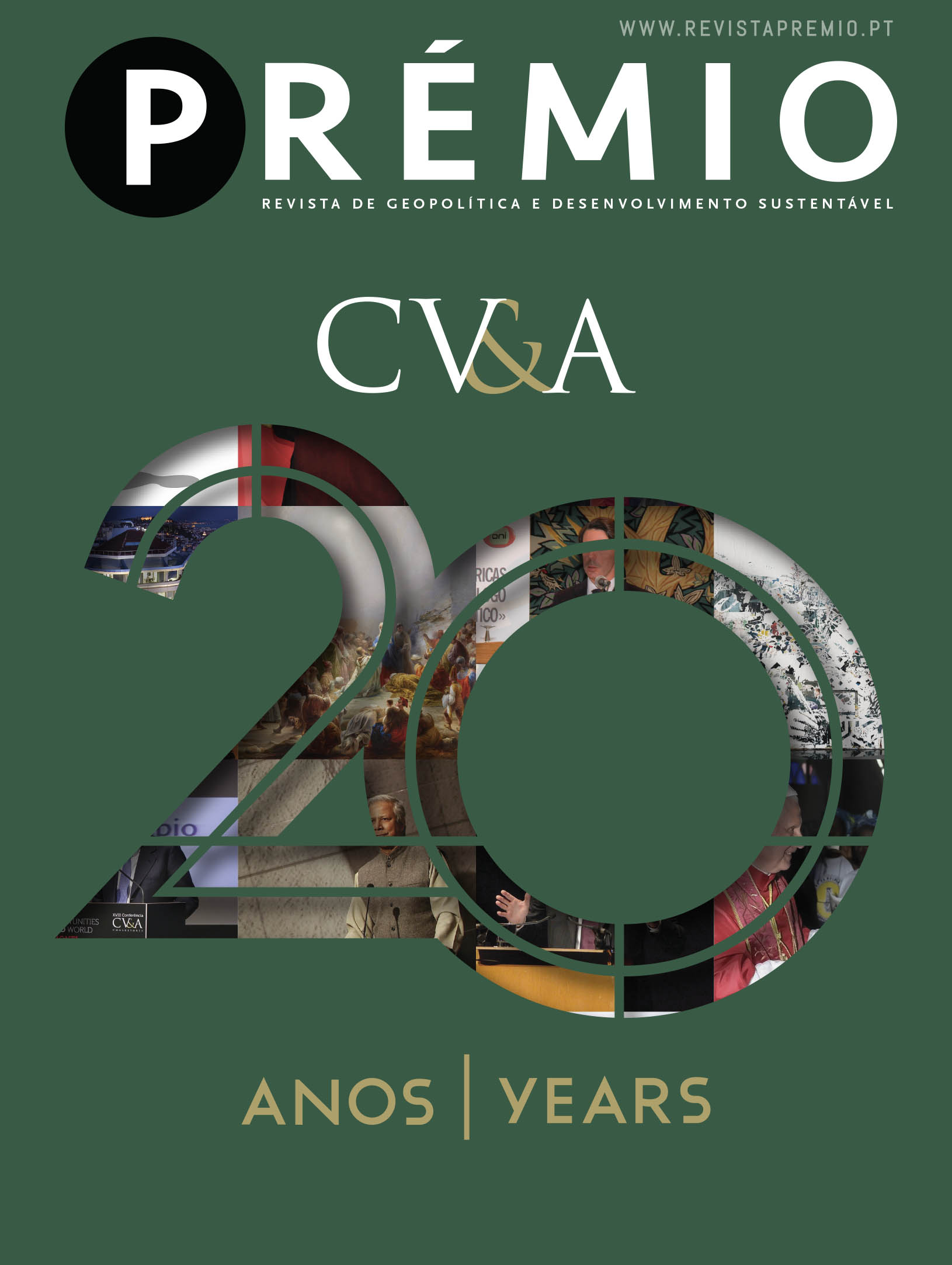

The author reporting from Bastanka

DAY 2

Late rains fell to make the driving between Odessa and Mykolaiev still more challenging. And getting some “conversation” out of Alex to help pass the kilometres.

The English language abilities of our driver were as basic as they were calm, available and turning out to be ever more competent to the extent we request his services day after day.

Alex was born 36 years ago in Lugansk, in the Donbas region that has been at war practically continuously since March 2014, which led this car salesman to grab his wife and son, then aged three, and move to a calmer region. He ended up choosing Odessa, the fourth largest city in Ukraine.

Eight years later, the war he fled seems to have caught up with him. Now, somewhat paradoxically, his role as a driver for international journalists sent to cover that same war has turned into his means for supporting his family.

– “It’s shocking when all your plans one day fall apart. When you don’t know what is going to be your own tomorrow!” – he recognised. “But we’re getting stronger, we believe in victory, we love and believe in our country and we will continue to live and work whatever happens!”.

– “Whatever happens!”… I find myself mulling over these words and how they fit in with so much of what we witness in the determination of those around us standing up to the invasion of their country. Vlad, our ‘fixer’ in this latest departure for Mykolaiev, signals to us that we have arrived at the location where a war veteran is awaiting us, a soldier who fought with the Soviet troops in Afghanistan and who now commands a sector in the city’s defence against Russian assault.

Vlad has good contacts in one of the most impenetrable circuits in the current conflict scenario in Ukraine; defence and security. And his contribution proves precious. Even when he then pushes his luck in unsuccessfully attempting to interfere in our editorial options for approaching the material collected.

Alex parks the car inside a courtyard that I then learn belongs to the city’s military hospital. The rain continues to fall. The three of us, myself, Rodrigo and Alex, with the filming equipment, follow behind Vlad who goes round a building and heads over to a group of soldiers in camouflage.

Our fixer makes the presentations. The majority of the military group back away to leave only three members close to us; one with a camera, another, the tallest in the group, a little further back with half a smile and the third – noticeably the senior commanding officer – who looked at me closely and would continue to do so until I gave a sign that the interview was over.

Oleg goes by the combat name of “Tro”. He remains undecided as to whether he will actually “speak to the journalists”. He wanted to know who we were, where we’d come from. And, in particular, “to sound us out”. This thing I’d describe as almost earthly, if not animalesque, that I learned in life to recognise in people who’d spent part of their time fighting for their own survival.

I know that I have to give him part of my comfort zone for him to accept me into his and I do so, groping my way forward, as if testing the stability of the floor with each step and evaluating my interlocutor out of the dignity with which one defends and values the openness granted.

Thus did I learn that he was a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, where he fought for the Soviets against the Mujahidin and was now a bulwark in the Ukrainian resistance in Mykolaeiv against the invading forces from Moscow. Such openness came after I had told him I was the son and grandson of officers and had attended military high school and understood from within the concepts and attitudes towards wearing the uniform of a country.

– “We’re trying to normalise the situation in all the ways we can. Our presence helps people to calm down”, explains “Tro” as regards the feat of having forced back the Russian offensive, which ended up positioning armoured vehicles in the city. “We cannot, however, stop all of the missiles that fly over us but we are doing everything we can to ensure the security of the city”.

But for a person who has already worn the uniform of the other side, his witness account comes as a shock.

– “You see what is happening in Mariupol. Almost completely destroyed. It’s not possible to believe in them. They lie to everybody, including to themselves. They are lying to you!” – he insists, his face becoming suddenly serious. “When I was in Afghanistan with the Soviets, I never imagined that this could happen; they are now showing a completely inhuman side. There is absolutely nothing human either in them or in their actions.”

– “…that was hell …” – he adds.

– “Not so much of a hell as here!” – A hell which, in the words of Oleg, does not even spare the weakest;

– “They are hitting and deliberately destroying the civilian population. They are lying. There is nothing sacred for them. I’m a veteran of Afghanistan, I know what war is. Just what is involved. And what they are doing here is not war. Just the actions of scum. They are killing our women, our children, the civilians, the elderly.”

The cost of any war… where you’re defeated from the outset…is humanism.

Hospital bombarded in Bashtanka

School bombarded in Zeleniy Guy

DAY 3

The “hint” given by Anna Zamazeeva, the President of the Mykholaiev Regional Council, who by chance had survived a Russian missile strike on the building housing the organisation that left 37 people dead with dozens of wounded.

Russian artillery hit the city hospital causing dozens of wounded. Alex easily found the location via Google maps and parked the car close to the gate used by the ambulances.

From a distance, there are no obvious signs of war but, as we walk towards the building, first the sandbag protected windows come into view and then followed by the impact of the projectiles. On this occasion, the air defence system intercepted a missile as it approached the building but the respective explosion caused severe damage to the pediatric ward and one serious injury.

Maria, our ‘fixer’, asks for permission to report on the event and the immediate response is negative. She insists, highlighting how it had been Zamazeeva who had identified the event. The doctor who was blocking our path asked for time to confer to one side with a colleague. A few minutes later, the pair returned. They said they did not want to be either identified or interviewed but did present the head of the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit who agreed to speak.

Andrey Krasyukov, by name, is a charming person. He turns up smiling. He asks us who we are, why we came, how we got there and, finally, whether we wanted to interview him inside or outside the building.

Rodrigo chooses inside, to better illustrate the image of clinical activity even while the scenario, as we then verify, is heavy. However, “it is what it is. It is in this environment that the clinical team works and patients are seen” – I believe, always aligning with the filming options of my colleague, a professional with a rare sensitivity and talent for this field.

– “This has become normal for us. We hear the explosions. We see the wounded. This has all become a new normal for us in these over two months of war. This is what we get to see,” – the clinical specialist accepted.

The daily bombardments test the resistance of the medical team right to the limit.

– “It’s very hard to see…they bring in children who have already died….we can do nothing. We see kids who have been injured, many of them seriously. They all receive help from our staff and we shall continue to do this here. (…) Yes, they are shelling, the bombs continue to fall but we do this work because they are children”.

A nurse calls for Andrey. He hears her, asks to be excused for a minute, follows her and the pair go through a door and we remain waiting in the corridor: attempting to block the space as little as possible for those passing by.

– “Come with me!” – the doctor has reappeared, framed by the doorway through which he’d headed. “There is a young man who wants to talk to you!”.

Rodrigo goes first as he always does so as to ensure that I do not “ruin the shots (filming)” by getting in the way. However, the doctor asks for us first to take off our coats and bulletproof jackets and put on a surgical gown before going into the room. We soon understand why.

Lying on a bed, wearing only underwear, with his right leg extended by a splint attached to his foot, a large bandage on the shin of the same leg, and the scars of recent surgery stapled to the exterior of his belly, there was a young, jaundiced looking adolescent.

Kirill is aged 16. He was out walking, in front of the hospital, when the missile exploded leaving his right foot almost ripped off his leg and hit in the chest by missile shrapnel. By a “miracle”, and the speed and talent of the medical intervention, he survived.

– “I was heading home when one of the projectiles came down in front of me. After this, everything began shaking… I lost a leg… well…I fell over, tried to stand up again but couldn’t” – the youth explains after having asked to speak to us on learning there was a team of foreign journalists in the hospital.

From his bed in Intensive Care, in front of a window blacked out by sandbags, he asked us to leave his suffering in anonymity;

“Thank you for coming here, risking your lives. Inform the world and help them understand what is now happening in my country”.

DAY 4

The silence prevailing in the car reflects the tension building up as we approach the frontline. Getting through the road blocks becomes impossible unless accompanied by members of the Ukrainian Territorial Defence.

Following days of contacts, Maria managed to get us one. She guaranteed us. However, on the day of the report, the hours began passing and with them the window of opportunity was closing.

Sat waiting while the spokesperson of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in Mykolaiev, Lieutenant-colonel Dmytro Pletenchuk, and Yuri, the Territorial Defence member secured by Maria, moved on from marinating their respective neurones in testosterone, in a cockerel fight over who was most in charge and of what.

Three hours later than planned, we were finally heading towards Zeleniy Guy, 10 kilometres from the zone already occupied by the Russians from where we had heard reports of schools and residential zones getting shelled and civilian cars getting ambushed by machine gunfire.

Such a scenario is confirmed to the extent we approach this rural town. Yuri and another soldier are in camouflage and with AK-47s in their laps in a vehicle in front of ours and opening the way at the checkpoints.

Just before the junction where the road turns left into the town, I spot a civilian car, grey in colour, riddled with bullet holes, with the doors open and the clothing scattered around the immediate vicinity. Yuri explains to us the occupants were killed in an ambush by Russian troops.

The violence only worsens after that. We take the left, pass three abandoned checkpoints, three burned out Ukrainian armoured vehicles and, immediately afterwards, our guide gives us the signal to stop. He gets out and heads on foot into a property with low walls.

The rumble of artillery could be heard. He continued onwards, unfazed. He points in front where there is a very large, three storey building with its centre pulverised by what appears to be the impact of a powerful explosion.

Yuri identifies how the building was a primary school; the Zelenogai School. The power of the missiles was such that there is a crater in which he fits standing up. And this left the classroom in ruins, with schools materials mixed up on the floor with the remains of walls and the slabs making up the upper floors threatening to give way.

– “There was a large scale bombardment here! In a school where local children studied”, he stresses while showing the inside of a classroom through a gap in the walls, where books and study materials lie mixed up on the floor with shards of broken window glass, chairs and destroyed finishings.

This bombardment did not ignore either the creche in the road running parallel to the primary school. And where I report live for that afternoon’s news next to walls destroyed by Russian artillery, while the sounds of nearby shelling grow more intense.

A few dozen metres away, on the other side of the street, one of the few remaining residents tells us what happened. He explains why he stayed behind: with the seven dogs of his neighbours who have in the meantime disappeared and with which he now inhabits the ruins of the town.

“How did I survive? I survived with the dogs in a basement. When they bombed, we would go down there!” – reports Alexander, with his two eyes clouded by cataracts. “We’re already used to it. We’re already able to distinguish from where and to where they ae firing”.

With the nearby artillery making itself felt, Yuri gives us the signal to rapidly exit the town. He leads us through green fields where wheat was growing, mixed in with unexploded ordinance….and, further on, the remains of Russian attack helicopters shot down by Ukrainian artillery.

A few metres away, an improvised grave;

– “This is where the Russian pilot of this helicopter is buried” – indicates Yuri towards the Russian military cap, placed on a stick to mark the site where the body of the invader is buried.

On one side of the road… death is settled… on the other… the paradox of the return to life. A few hundred metres away from the wreckage of the Russian helicopter, on the other side of the earthen road, an agricultural worker was raising dust as he turned the earth with another labourer looking on.

We go over to them. Volodymir is his name, I learn, and he agrees to be interviewed for our report; helping us to understand where he goes, where they go, to seek out such resilience:

– “As I say…we’re getting by…they bombard, we sow. They bomb again, we sow again so that we always have something to eat”.

Note: These are only four accounts in a text format of 26 reports made by the author throughout the 29 days of his deployment to cover events in Ukraine.

Photos courteously granted by the author